Fasting Before Surgery: Questioning the Evidence Behind the Guidelines

A catchy headline suggesting fasting before surgery may be unnecessary is yet another catchy headline without substance

An article was published last week making headlines for its claim that fasting before surgery may be unnecessary. While I love it when people challenge long-held beliefs, especially ones based on weak or limited evidence, this paper leaves a lot to be desired.

The article by Lam and colleagues is a systematic review and meta-analysis examining aspiration rates between different fasting conditions. The authors were critical of prior research that focused on surrogate outcomes such as residual gastric contents or gastric pH claiming these endpoints have never been shown to predict aspiration in humans. Their main argument appears to be that more research is needed to recommend fasting. However, it is unclear whether they are arguing for NPO times shorter than currently recommended 2 hours for clears or if they are arguing to encourage more people to follow guidelines allowing clear liquids up to 2 hours before surgery?

Lam and colleagues included 17 studies from January 2016 to December 2023 with 801 patients in the experimental group and 990 in the control group. The meta-analysis was confusing because some studies compared American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) fasting guidelines to non-fasted patients and others compared strict NPO after midnight to clear liquids up to 2 hours before surgery (the current ASA recommendations). The analysis did not clearly separate patients who were fasting and patients who were not.

The authors excluded studies prior to 2016 because:

The systematic review that was performed to support the 2017 ASA fasting guideline did not report any studies of witnessed aspiration, we began our search 1 year before the guideline's publication assuming that (1) there were few studies reporting aspiration as an outcome for the time period that the literature was reviewed by the ASA and (2) older literature would not apply to current anesthesia practice.”

The problems I see with this argument are 1) multiple studies exist prior to 2016 looking at aspiration [1] [2] [3] [4], and 2) even though anesthetic medications have evolved, the act of removing a patient’s reflexes thereby increasing the likelihood of aspiration has not changed.

Statistical power

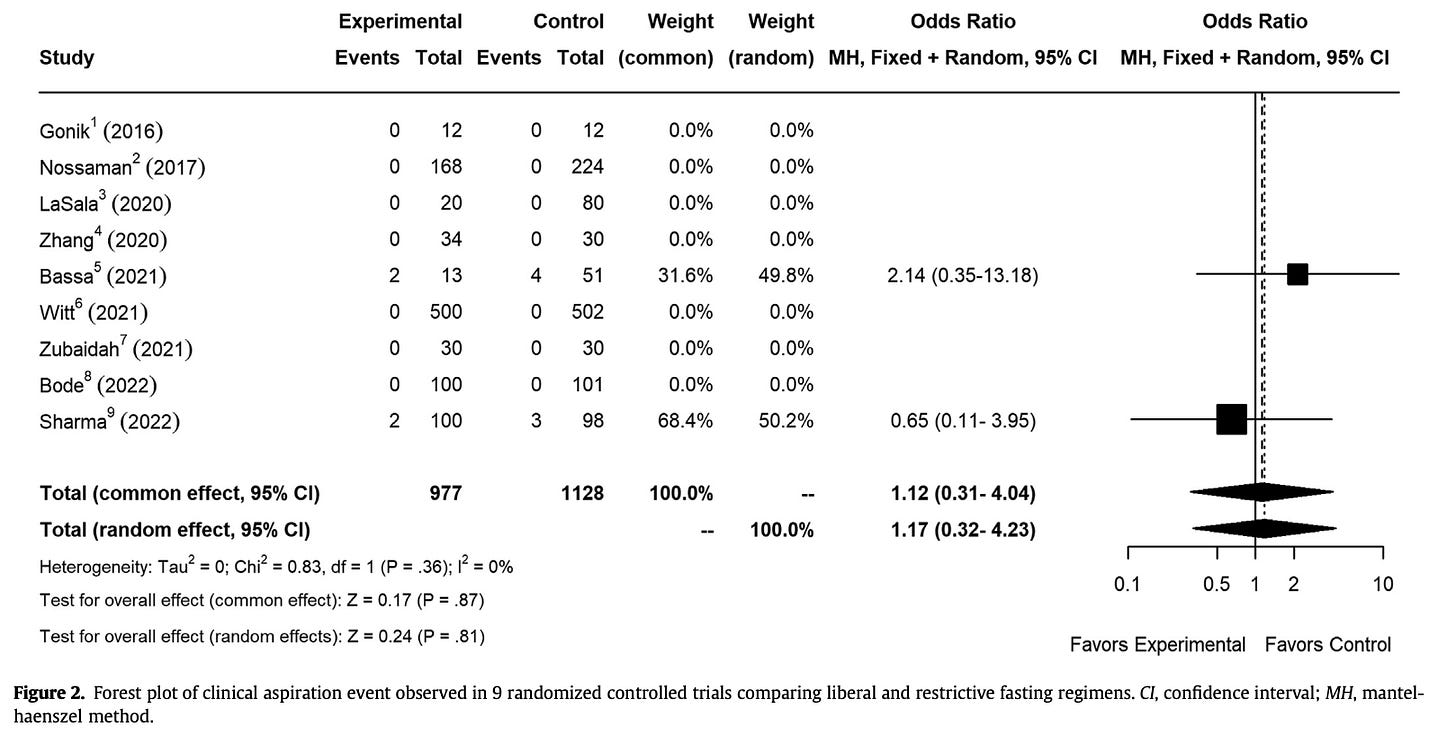

In support of the authors’ hypothesis, the study found no statistically significant difference between aspiration events in the experimental group (n = 4, 0.50%) and the control group (n = 7, 0.71%). The absolute difference between the groups is 0.0021. This is very small. To detect a statistically significant difference with ⍺ = 0.05, a power calculation estimates each group would need about 21,405 patients. This is roughly 24x more patients than were included in this study. Enrollment of this size is precisely why surrogate endpoints are so often used.

Note the wide confidence interval suggesting the lack of power.

A type II error occurs when a study claims there was no difference when in fact there was a difference. It is impossible to say from this research if we would find a difference between the groups, so we cannot say that a type II error was committed. These results are inconclusive.1 However, the authors erroneously conclude, “The lack of evidence demonstrating a relationship between fasting and aspiration suggests that fasting policies should be liberalized…”

Looking deeper at the included studies

Only two of the included 17 studies were identified as having aspiration events. Of these, two aspiration events in the experiential group and four in the control group were from a study looking at aspiration in mechanically ventilated SICU patients who had tube feeds stopped for < 6 or ≥ 6 hours prior to surgery. The paper describes: "aspiration was identified in the progress notes and the discharge summary." It does not detail if aspiration events occurred before, during, or after intubation, during anesthesia, or while not intubated. Nor does it detail whether these patients aspirated around the cuffed ETTs. Generalizing from an intubated ICU population to fasting guidelines for non-intubated patients undergoing non-emergency surgery seems precarious.

The only other study with "aspiration" events showed an event rate of 2% (n = 2) in the experimental group and 3% (n = 3) in the control group. This rate is roughly 100x that reported in prior literature of 0.01% - 0.24%. This should give anyone pause, and indeed the devil is in the details. Sharma et al. compared strict NPO after midnight to patients allowed to have clear liquids until 2 hours before surgery (current ASA guidelines). They write:

To evaluate regurgitation during anesthesia, a piece of turnsole paper was inserted at the end of the pharynx, and in case of color change toward acidic pH, an event of regurgitation was reported as positive.

Although Table 3 lists two aspirations in the experimental group and three in the control group, the discussion indicates these events were simply positive color change on the pH paper rather than pulmonary aspirations. The authors report, “In our study, we found no evidence of aspiration or related events in any patient in both groups.”

In summary, one article showed aspiration events in a different patient population and the other explicitly stated it did not have aspiration events. What are we to make of a meta-analysis which did not clearly sort the fasting groups and which had no [relevant] events in either arm?

What is the argument in favor of liberalizing fasting times?

I am unconvinced that fasting causes acute harm. The citations the authors included do not support their claims that:

Fasting adversely affects patients by its impact on either health-related quality of life, postoperative outcomes, or metabolic complications such as hypoglycemia and insulin resistance.

One reference showed higher patient satisfaction when allowed to consume clear carbohydrate beverages up to 2 hours before surgery. This is in line with current fasting guidelines. Another reference showed surgical outcomes were improved with decreasing percentages of HbA1c—which, while important, is not relevant to acute fasting. The third citation found acute increases in insulin resistance when patients were fasted for 24-to-72-hours, discussing this largely in the context of postoperative fasting.

Exercise acutely causes many changes which could be perceived in isolation as harmful. It causes hypertension, tachycardia, sympathetic stimulation, inflammation, and increased oxidative stress. Yet we know exercise is one of the most potent interventions for health. Can it truly be argued that acute insulin-resistance from an overnight fast is harmful? Furthermore, humans fast for more than eight hours every night without metabolic harm. Intermittent fasting or time-restricted eating is commonplace and has been shown in multiple studies to improve weight and metabolic markers (although the effect is more likely due to overall caloric restriction rather than timing of food consumption).

For patients taking insulin, there is a real concern of hypoglycemia while fasting. Beyond this, is there actually clinically meaningful harm from short-term fasting?

The argument in favor of fasting

Aspiration is a rare event with potentially catastrophic consequences including death. As the saying goes, no one has performed a randomized controlled trial in humans looking at the effectiveness of parachutes. Do we need to perform an RCT to conclude that fasting is the safest option? Lack of evidence does not necessarily mean there is lack of benefit.

However, we now know from the recent research on GLP-1 receptor agonists that many more patients are presenting to surgery with increased residual gastric contents. So far, rates of aspiration have not been shown to be significantly above historical averages. For this reason, I am open to the idea that there may be a higher cutoff of residual gastric volume which is considered low risk for aspiration. Perhaps fasting is not as critical as we have led ourselves to believe. More research should be done. In the meantime, I still think the most risk-mitigating approach is to have people fast prior to surgery.2

As the authors note, “anesthesia-associated aspiration is and always was rare.” Rare events will always be difficult to study. When rare events can have catastrophic outcomes, it will always be prudent to safeguard against them. While the authors may not have committed a type 2 error, they still fooled themselves into thinking they had evidence of no benefit when what they really had were inconclusive results—a significantly less splashy headline. As Richard Feynman once said, “The first principle [of science] is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.”

The authors almost said this in the results section: “No definitive statistical conclusions can be made regarding the risk of clinical aspiration resulting from the shorter duration of less intense preprocedural fasting regimens…”

And have patients on GLP-1 RAs fast even longer