How should GLP-1 receptor agonists be managed in the perioperative period?

Society guidelines have left clinicians with some questionable recommendations

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), such as semaglutide and tirzepatide, are becoming increasingly prescribed to treat diabetes mellitus and obesity. They work by increasing insulin secretion, decreasing appetite, and slowing gastric emptying. Gastric emptying often normalizes once a patient is on a stable dose. However, many patients have been found to have residual gastric contents after fasting, even when on stable doses.

In June 2023, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) released a consensus-based guideline on the management of patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists. The concern with these medications is that the delayed gastric emptying leads to residual gastric contents, which may increase the risk of aspiration. This original guideline recommends holding one dose of the GLP-1 RA prior to surgery, but does not recommend changing fasting times.

In anesthesia, one of the first risks to manage in patients is that of aspiration. Fasting guidelines (also called NPO guidelines) are strictly adhered to for this very reason. The NPO guidelines have always had the caveat that patients with delayed gastric emptying may need longer fasting times. The guidelines state, “Anesthesiologists should recognize that these conditions can increase the likelihood of regurgitation and pulmonary aspiration and should modify these guidelines based upon their clinical judgment.” A previous version states, “The guidelines may not apply to, or may need to be modified for, patients with coexisting diseases or conditions that can affect gastric emptying or fluid volume (e.g., pregnancy, obesity, diabetes, hiatal hernia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, ileus or bowel obstruction, emergency care, or enteral tube feeding) and patients in whom airway management might be difficult.”

Requiring patients to abstain from food for longer than 8 hours, even if the optimal duration was unknown, would have been the most cautious approach, even if it was unenjoyable for patients. Instead of taking this approach, the ASA stated, “There is no evidence to suggest the optimal duration of fasting for patients on GLP-1 agonists. Therefore, until we have adequate evidence, we suggest following the current ASA fasting guidelines.” The irony of this is that in the very same guidelines they recommended holding one dose of GLP-1 RAs prior to surgery despite having no evidence that this would minimize residual gastric contents.

What is the harm in holding a dose of GLP-1 receptor agonists?

Every GLP-1 receptor agonist causes delayed gastric emptying. When patients start on these medications, they often experience nausea and vomiting. For this reason, patients are started on the lowest dose and slowly dose-escalated no faster than one increment every four weeks as patients begin to tolerate the medications and the side effects diminish. With each escalating dose, the side effects often temporarily return. When two or more doses of the medication are skipped, a person can lose tolerance, increasing the risk of severe side effects once the GLP-1 receptor agonist is resumed. In this situation, it is often recommended to revert to a lower dose and re-escalate after four weeks. This can pose problems such as needing a new prescription, cost to the patient, worsened glucose control, and weight regain. The logistical problems could lead to even more time off the medications.

In patients receiving GLP-1 RAs for diabetes, the most obvious harm from holding them is poorly controlled blood glucose. Given the risk of complications from uncontrolled diabetes, such as the increased risk of wound infections from hyperglycemia, it would be in a patient’s best interest to continue these medications in the perioperative setting.

Holding GLP-1 RAs for five half-lives can lead to normalization of gastric emptying. For semaglutide dosed once weekly, this amounts to being off the medication for five weeks. Again, the downsides of poorly controlled glucose and weight regain make this a poor approach to management since both hyperglycemia and increasing body mass index are associated with worse perioperative outcomes.

The ASA’s initial recommendation to hold one dose of GLP-1 RAs is all downside with no benefit.

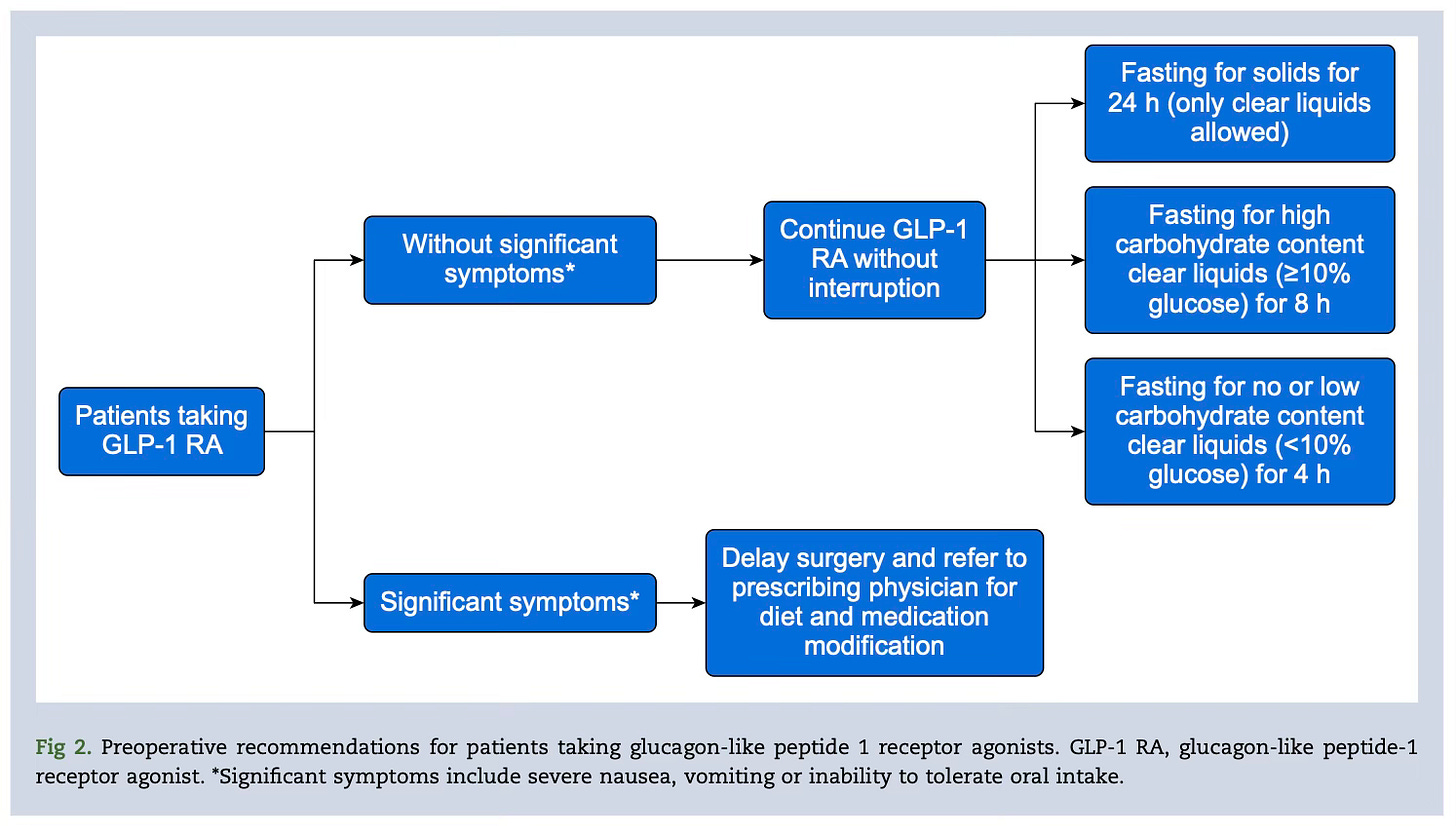

The ASA revised its practice guideline in December 2024, issuing a multi-society guideline. One important change is that they state, “GLP-1 RA therapy may be continued preoperatively in patients without elevated risk of delayed gastric emptying.” The risk factors they state include: escalation phase of dosing, higher dose, weekly dosing (as opposed to daily dosing), gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dyspepsia, constipation), and medical conditions that may cause delayed gastric emptying. Who taking a GLP-1 RA is not at increased risk of delayed gastric emptying when that is the very mechanism by which the drugs work? It is important to note that patients who fail to meet all of these risk factors (i.e., patients on stable doses without gastrointestinal symptoms) can still have delayed gastric emptying.

This part of the guideline is silly because there is no way to risk stratify these patients using the stated risk factors. A recent study found no correlation between short- and long-acting of GLP-1 RA, dose, and duration of use with a percentage of patients in all categories experiencing residual gastric contents. Instances of delayed gastric emptying can occur even after patients have been taking GLP-1 RAs for more than three years. The idea that one can accurately identify delayed gastric emptying without performing imaging (such as bedside gastric ultrasound) is not rooted in reality.

The second part of the guideline is more useful, suggesting that patients could undergo 24-hour liquid fasts or rapid sequence induction to minimize risks of aspiration. Ultimately, these actions are left up to shared decision-making.

Shortly after these guidelines were released, the British Association of Anaesthetists released guidelines in January 2025 with similar recommendations. They recommend continuing GLP-1 RAs in the perioperative setting without giving any exceptions. They also note that “upper gastrointestinal symptoms alone should not be used to determine gastric content.” In my opinion, these guidelines offer much better and clearer recommendations.

What does the evidence say?

Perhaps the best single paper on this topic comes from Oprea and colleagues and was published in the British Journal of Anaesthesia in July 2025. Their group, the Society for Perioperative Assessment and Quality Improvement (SPAQI), released their own multidisciplinary consensus guidelines along with a review of the current evidence.

Without making this post needlessly long, I will briefly summarize the evidence.

Most of the aspirations in the literature occurred during MAC (i.e., sedation) cases.

One study showed aspiration pneumonia events occurred at a similar rate to a historical cohort (4.6/10,000 vs. 4.8/10,000).

Multiple studies, usually done during endoscopies (EGDs) with or without colonoscopies, have shown that patients on GLP-1 receptor agonists have residual gastric contents when fasting from solids for 8 hours (70% of patients, n=10) and when fasting from solids for up to 16 hours (13.1% after 10 hr, n=84; 5.4% after 12 hr, n=205; 56% after 13 hr, n=62; 24.2% after 14 hr, n=33; 19% after 16 hr, n=90).

Patients with obesity and diabetes who were not on GLP-1 receptor agonists also had residual gastric contents at an alarmingly high rate.

In obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM): 5.1% had residual gastric contents after no solids for 14 hr, n=371.

In obesity: 20% after 8 hr, n=10.

In T2DM: 0.49% after 13 hr, n=205.

In obesity and T2DM: 5.0% after 16 hr, n=102.

Only one study showed no residual gastric contents in all patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists after having the patients fast from solids for 24 hours and from liquids for 12 hours (n=57).

We know that patients taking GLP-1 RAs have an increased incidence of residual gastric contents even when fasting. But what was an even bigger insight for me was the percentage of patients not on GLP-1 RAs who also had increased residual gastric contents. This could be interpreted as alarming and signaling that we should lengthen NPO times, particularly in diabetic patients who may have undiagnosed gastroparesis, or it could potentially be seen as reassuring, indicating that maybe a low volume of gastric contents isn’t as big of a risk factor for aspiration as once thought.1

The authors of this paper recommend that patients be fasted from solid food for 24 hours. This was based on the one study which failed to find residual gastric contents when patients performed a 24 hour fast from solid food and a 12 hour fast from liquids. The authors arbitrarily (and acknowledge that it is arbitrary) recommend fasting from liquids for 4-8 hours (4 hours for no/low-carbohydrate clear liquids and 8 hours for high-carbohydrate clear liquids). The optimal timing for fasting from clear liquids alone is unclear because all the included studies also had patients consuming solids.

Some countries, such as Australia and New Zealand, have adopted guidelines similar to these recommendations, asking patients to fast from solids for 24 hours.

What amount of residual gastric contents increases the risk of aspiration?

Perhaps this is the question we should be asking. Unfortunately, I do not have an answer for you. What remains unclear is whether patients taking GLP-1 RAs have an increased risk of aspiration. The data are conflicting, yet, most studies have not shown an increased incidence of aspiration.

One meta-analysis (April 2025) found no difference in incidence of aspiration (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.87–1.25) despite the patients taking GLP-1 RAs having a higher incidence of residual gastric contents. However, the authors note that the certainty of evidence was low. Another meta-analysis (July 2025), looking only at endoscopies, found an increased incidence of pulmonary aspiration among patients taking GLP-1 RAs (OR 2.29, 95% CI 1.36-3.87).

I see people arguing that because we have not seen a clear increase in aspiration events, there is no need to treat these patients differently. I would be cautious with that approach. Because aspiration is a rare event, it may be a long time before we can know with high-quality evidence whether GLP-1 RA use increases aspiration risk. The precautionary principle would suggest we do our best to prevent aspiration events in these patients unless we have clear, high-quality evidence that patients taking GLP-1 RAs are not at increased risk of aspiration.

Where does this leave us?

What is clear is that patients should continue taking their GLP-1 receptor agonists in the perioperative period. There is no benefit in holding one dose of these medications and there is potential harm.

If fasting guidelines are meant to minimize residual gastric contents then the clear guidance would be to have these patients undergo prolonged fasting from solid food. Based on the available evidence, fasting from solids for 24 hours would be necessary. If fasting guidelines are instead meant to minimize aspiration events without respect to residual gastric contents, then I think we need to start questioning what amount of residual gastric contents (and what type) are clinically significant.2

Opera and colleagues published a correspondence this month addressing some of the criticisms of their article. It is a well-written response, and one I highly recommend you read even if you do not read the primary paper(s). They write:

“The current literature supports modifying fasting recommendations for patients taking GLP-1 RAs as the most important mitigating factor. Although rare, aspiration pneumonia can result in hospitalisation, ICU admission, increased healthcare costs, and even death. When faced with such a prospect, a 24-h clear liquid diet does not seem to pose an equal risk or inconvenience.”

The bottom line is this: the most risk-mitigating approach based on the evidence would be to have patients fast for longer (ideally no solids for 24 hours and no liquids for perhaps longer than 2 hours). Would that be unpopular? Absolutely. Would it be safer? That remains less clear.

What are your thoughts on this topic? What are your organizations recommending?

I am trying to play a little devil’s advocate here. An important question to ask, and one we may never have a clear answer to, is “what amount of residual gastric contents increases the risk of aspiration?” Surely, type of gastric contents (liquid or solid) also matters.

Solids almost certainly pose more of an aspiration risk than liquids. What amount of liquid gastric contents clearly increases aspiration risk is something that seems, from my reding of this literature, to be less clear. Research in pediatric patients supports a “sip-til-send” approach to clear liquids without an increase in aspiration events.

Nice summary of a topic that’s still evolving but definitely highly relevant for clinical practice. The indications for GLP1 agonists seem to be increasing by the day. I do feel, however, gastric ultrasound deserves a mention here. What are your thoughts on if it fits in the preoperative workflow?