What should we conclude from the RSI Trial comparing ketamine to etomidate for intubation?

Maybe nothing…

For most of my career as a paramedic, etomidate was the only induction agent I had. Sure, I had midazolam and fentanyl, but not in high enough quantities to intubate. Only toward the end of my medic career was ketamine available. When I started doing anesthesia, I was already solidly in the camp of using etomidate for hypotensive patients.

However, as I learned more, the controversy over etomidate potentially increasing mortality in critically ill patients made me pause. I came to think that ketamine likely provided all of the hemodynamic benefits without the downside of adrenal suppression (whether this is clinically significant remains unclear). Despite recent studies failing to show an increase in mortality when using etomidate for intubation, my approach of minimizing potential risks led me to largely avoid it in favor of ketamine. Will the results of the newly published RSI trial push me back to using etomidate for intubation in critically ill patients?

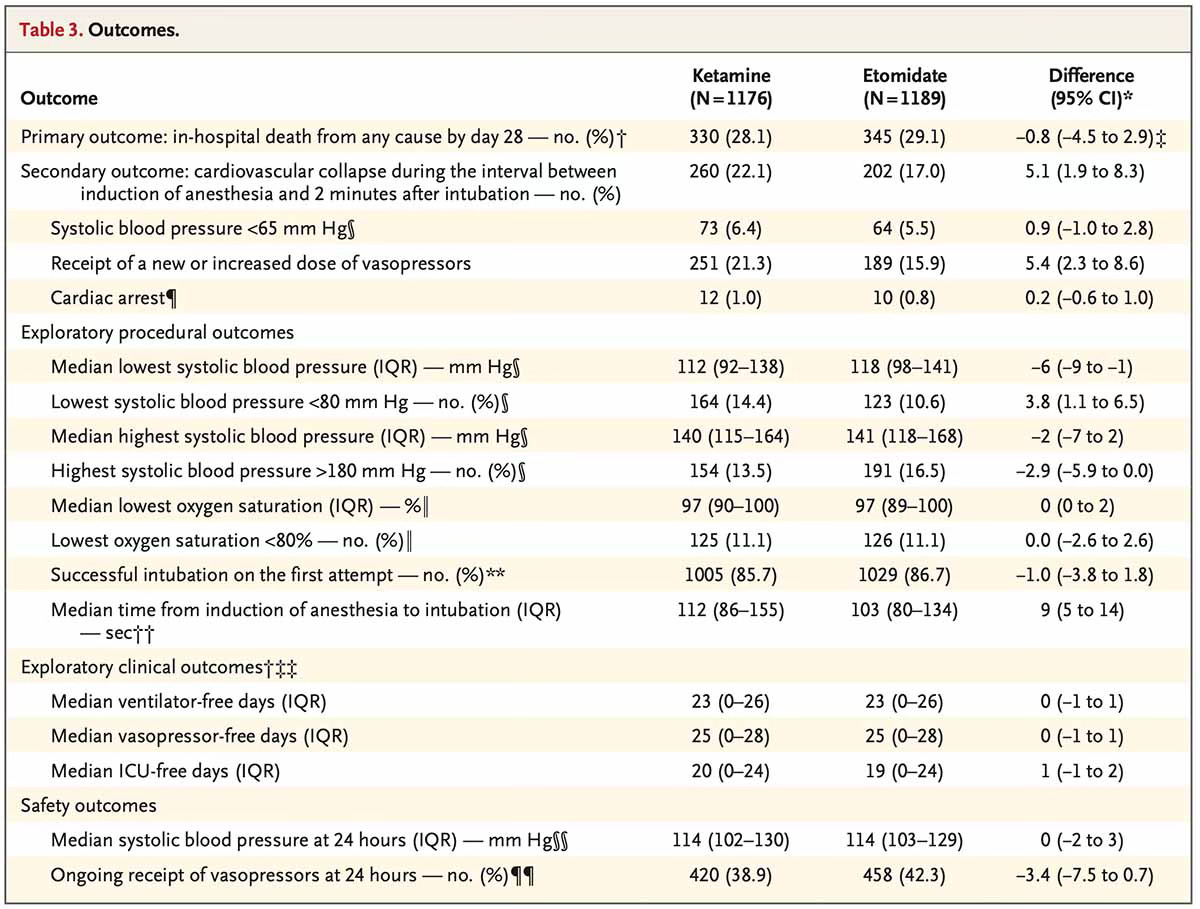

Both EMCrit and PulmCrit have great discussions on this trial, and The Bottom Line has a detailed breakdown of the numbers. I would direct readers to their posts for a more in-depth analysis. In short, this was a multi-center trial that randomized 2,365 emergency department and ICU patients to receive either ketamine or etomidate for intubation. The primary outcome was 28-day mortality, with a secondary outcome of cardiovascular collapse—a composite of systolic blood pressure < 65 mmHg between induction and two minutes post-induction, new or increased vasopressor requirement, or cardiac arrest.

A non-significant 1% increase in mortality was seen with etomidate (28.1% with ketamine vs 29.1% with etomidate). I want to be reassured by this evidence, but since the study was powered to detect a larger mortality difference of 5.2%, it remains possible etomidate increases mortality. As Josh Farkas writes, “Searching out tiny mortality differences pushes us to the edge of the scientific method, because these hypotheses aren’t testable. This is almost more of a philosophical question than a scientific one. Ultimately, I don’t know exactly what to make of this.” I don’t think this trial moves the evidentiary needle on this topic.

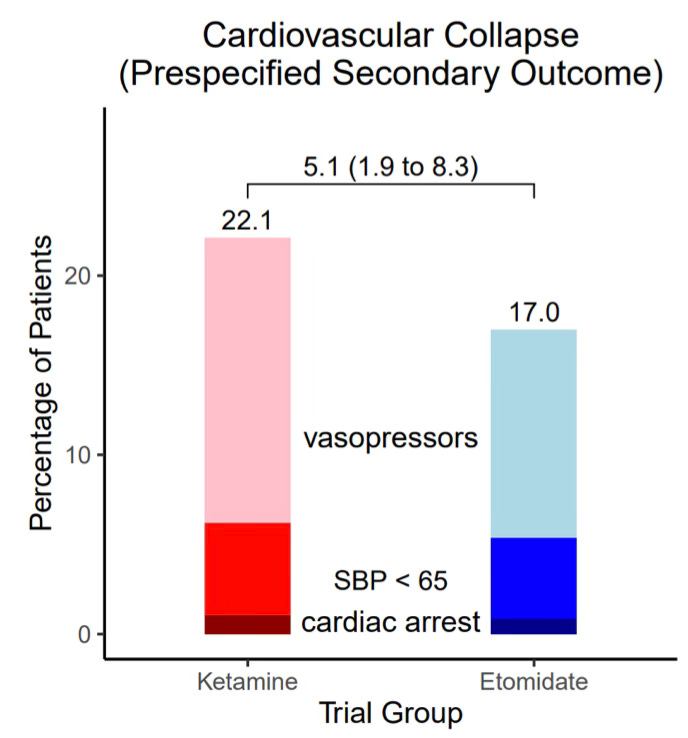

A statistically significant increased rate of cardiovascular collapse (see above definition) was seen in the ketamine group (22.1%) compared to the etomidate group (17.0%), with an absolute risk difference of 5.1% (95% CI, 1.9 to 8.3). How meaningful is this? Most of the difference in the composite secondary endpoint was due to new or increased vasopressor use in the ketamine group (21.3% vs 15.9%; see image below).1 This difference could be due to differing patient characteristics. In the subgroup analysis, there were more patients in the ketamine group with sepsis (30.6% vs 20.9%) and with APACHE II scores ≥ 20 (31.4% vs 20.7%).

Perhaps a bigger reason there was more hypotension in the ketamine group was the drug dosing. Ketamine was dosed from 1.0-2.0 mg/kg of actual body weight, and etomidate was dosed at 0.2-0.3 mg/kg of actual body weight. The median dose of ketamine was 140 mg, 1.6 mg/kg (IQR 1.4-2.0 mg/kg), and the median dose of etomidate was 20 mg, 0.28 mg/kg (IQR 0.24-0.31 mg/kg). A large percentage of patients in both arms received greater than the maximum recommended doses of their respective induction agents.2 Only 5.8% of patients in the ketamine group received < 1.0 mg/kg. From my perspective, it would be difficult to exclude ketamine (over)dosing as the primary driver of increased post-induction hypotension.

What should we conclude from the RSI trial?

Unfortunately, it was underpowered to detect a mortality difference, so concerns about etomidate’s effect on mortality remain unresolved. This was a well-done trial with, in my mind, one major exception—the dosing of ketamine. Maybe ketamine causes more hypotension or maybe it was due to the higher dosing used. In critically ill patients, I would use ≤ 1 mg/kg of ketamine; this represents < 25% of the patients in the ketamine group. I wanted this trial to give me evidence to use etomidate again, but instead I’m left with more questions than answers.

What are your thoughts? Is this trial going to change your practice?

Of note, more patients received vasopressors at intubation in the etomidate group (19.7%) than the ketamine group (17.6%). Could the open-label nature of the trial have led clinicians to give more vasopressors up front when administering etomidate?

The percentage looks to be around 25%, but it is difficult to be precise because of the way the authors grouped the data in the supplemental.